Direct Fusion Drive to Mars: The Starfire Architecture for Fast Human Transit

Sixty-four days to Mars isn’t a slogan—it’s a design constraint disguised as a destination. In Layla Mohsen’s telling, Princeton Satellite Systems’ Direct Fusion Drive concept isn’t chasing speed for bragging rights; it’s chasing speed because deep space is a slow poison. Cut the transit time hard enough, pre-build the habitat before anyone arrives, and the whole Mars problem starts to look less like a survival marathon and more like transportation—if the reactor at the center of it all can actually be made real.

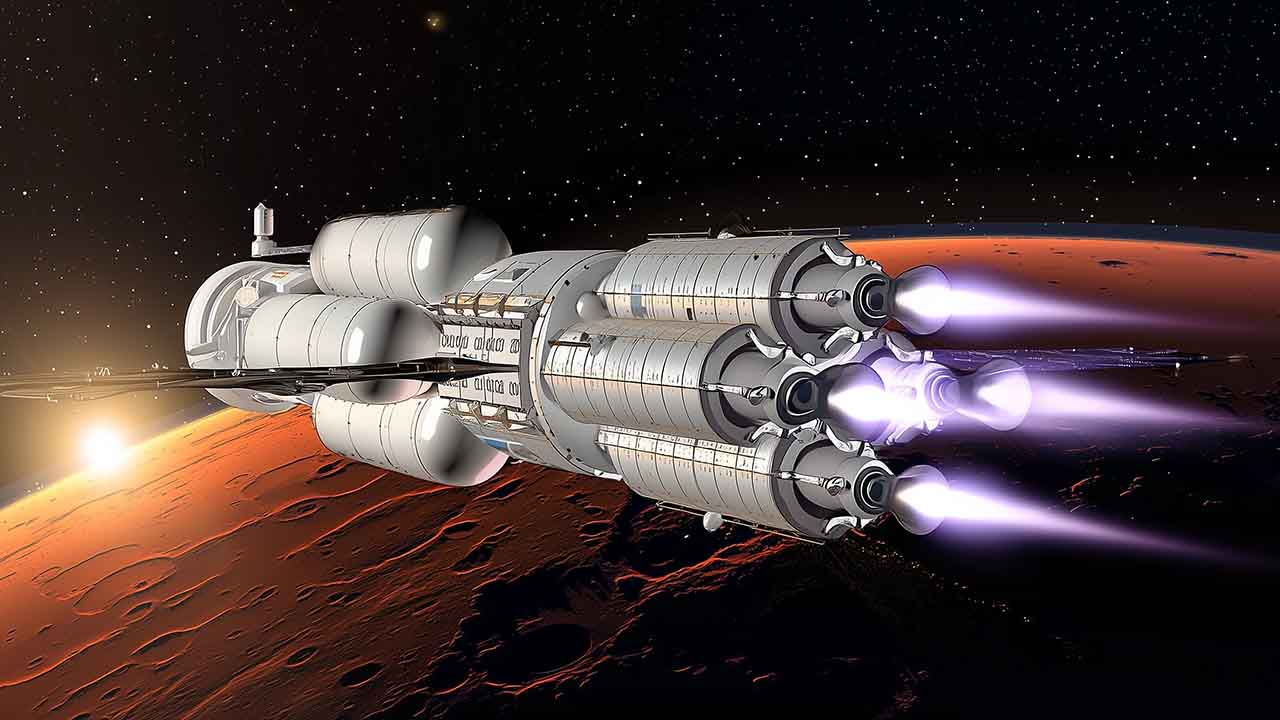

64 Days To Mars Using Direct Fusion Drive Propulsion

There’s a reason Mars plans keep turning into endurance tests: space is not just far, it’s slow. A crew can have the best life support, the best training, the best systems engineering—and still lose the mission to the quiet accumulation of exposure: radiation, microgravity, isolation, and plain old time. Beyond Earth’s protective magnetic cocoon, the environment becomes an always-on background of galactic cosmic rays plus intermittent solar events, and duration is the multiplier that turns “manageable” into “mission-defining.”

That’s why the most provocative part of Layla Mohsen’s Mars concept isn’t the renderings or the hardware vocabulary—it’s a number: 64 days. In the transcript, she frames the mission architecture as being deliberately engineered around that threshold because it’s meant to reduce crew exposure during the most vulnerable phase of the journey: deep-space transit. The concept is blunt about why this matters: time isn’t a scheduling issue in deep space—it’s a biological variable.

The architecture isn’t “fusion because fusion is cool.” It’s “fusion because biology is a constraint.” The propulsion system exists to bend time downward—to shrink the part of the mission where the crew is most exposed and least able to fix anything if systems drift. Fast transit becomes a risk-reduction strategy, not a futuristic flourish.

Mohsen’s framing makes the wager clear: if the trip can be made short enough, the entire tone of human Mars exploration changes—from a long, fragile survival marathon into something that starts to resemble transportation. The whole story of Princeton Satellite Systems’ approach is essentially about whether that pivot is real—or whether it remains, for now, a compelling sketch of a future that still has to be built.

Why “Seven to Ten Months” Became the Default

For decades, the implicit baseline for getting to Mars has been measured in months, not weeks. Mainstream Mars transfer timelines are commonly described in the neighborhood of seven to ten months, depending on mission design and launch-window timing. That estimate isn’t a failure of imagination; it’s the consequence of optimizing for energy, propellant, and the realities of chemical propulsion.

A minimum-energy trajectory is an engineer’s comfort zone: it’s efficient in propellant terms, easier on systems, and fits the logic of launch windows. But it also makes the crew pay in exposure time. When the ship is coasting for most of a year, the mission becomes less about “going to Mars” and more about “staying medically intact while drifting through a radiation field.”

That tension—efficient trajectory versus fast trajectory—shows up everywhere in Mars planning. The more travel time is compressed, the more the propulsion system has to do: more sustained thrust, more energy, more thermal management, more everything. Even when timelines can be shortened, the engineering cost has to be weighed against the biological benefit.

Mohsen’s concept starts by answering that question with a decisive “yes.” In her telling, the whole point of the mission design is to squeeze the crew travel time down until it meaningfully changes health risk—and then redesign everything else around the consequences of that decision.

Starfire: A Fusion Reactor That Wants to Be an Engine

Princeton Satellite Systems calls the enabling technology Starfire—a compact fusion system intended to operate in a dual mode: power plant and propulsion system. Mohsen describes it as a linear, compact architecture “less than 2 meters in diameter,” designed to deliver roughly 1 to 10 megawatts, and built around a different confinement approach than the big toroidal tokamaks and stellarators most people associate with fusion.

“Starfire is a compact nuclear fusion reactor. It has a dual mode so it can be used as a power plant and it could also be used as a propulsion system. It uses advanced aneutronic fuels. It’s less than 2 meters in diameter, and it’s meant to deliver 1 to 10 megawatts of power.” – Layla Mohsen

In PSS’s own public language, Starfire is the updated name for what earlier materials called the Direct Fusion Drive (DFD)—a direct-drive fusion-powered rocket engine concept meant to produce both power and thrust. That continuity matters because it anchors the Mars discussion in a longer arc of published concept work rather than a brand-new idea that appeared out of nowhere.

Mohsen also emphasizes something mission designers obsess over: flexibility. She argues that a fusion propulsion system in this class has high specific power, can be tuned for mission design needs, and—crucially—can be reused, turning a “one-shot mission vehicle” into something closer to infrastructure.

If the marketing is stripped away, the implied offer is simple: a single machine that acts like the beating heart of the mission—propelling the crew quickly when time matters, and then becoming a power source that makes the surface phase and the return phase far more plausible. That is the kind of promise that, if it’s real, forces every other Mars architecture to respond.

PFRC and the Rotating Magnetic Field Trick

Starfire’s “different architecture” isn’t just a shape; it’s a particular plasma-confinement lineage. PSS ties its work to the Princeton Field-Reversed Configuration (PFRC) concept, a compact approach associated with Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory research that uses radio-frequency methods to heat plasma and drive current, alongside magnetic mirrors to help confine particles. The basic proposition is that this geometry can deliver a compact reactor topology that’s better suited to spacecraft than massive toroidal machines.

In Mohsen’s walkthrough, the core mechanism is the rotating magnetic field (RMF) system near RF antennas. She explains that the RMF induces an azimuthal electric field, which drives a closed current loop in the plasma. That current generates a magnetic field opposing the background mirror field—creating the field-reversed configuration (FRC) where fusion reactions are intended to occur.

Her description sketches the physical layout in plain language: superconducting mirror magnets; a linear array of superconducting coils; RF antennas; and a vacuum vessel with RF coupling details. The point isn’t that listeners should memorize parts—it’s that the design aims to be compact and direct, with the heating/current-drive method deeply integrated into confinement rather than bolted on as an afterthought.

That integration shows up in PSS’s public Mars-mission framing as well: an FRC core heated with an odd-parity RMF method, surrounded by plasma flow that extracts energy and provides a way to trade thrust and exhaust velocity. The consistency between Mohsen’s verbal explanation and the published concept story is part of what makes it legible: it’s not just “fusion vibes”; it’s a coherent explanation of how the machine is supposed to be structured.

Fuel Choices: D–He³, “Not Completely Aneutronic,” and What Gets Extracted

Any fusion-to-Mars story eventually hits the fuel question, because fuel determines neutron production, shielding burden, and how survivable the hardware is over time. Mohsen says Starfire uses deuterium–helium-3 (D–He³) fuel and stresses that it is not completely aneutronic because there are side D–D reactions—but she argues the design aims to prevent neutron-related problems “as much as possible.”

In the best-case framing, that means trading the easier ignition conditions of D–T for a fuel cycle with less punishing neutron wall load. For a crewed spacecraft, neutron management becomes mass management, and mass management becomes mission design. The fuel choice isn’t a detail; it’s the hinge that decides whether “fast Mars” is feasible without turning the vehicle into a flying bunker.

Mohsen adds an operational nuance that is central to their neutron-mitigation story: the scrape-off layer. In her description, this region is where lower-temperature plasma mixes with reaction ash, and it’s also where the design tries to prevent D–D side reactions from producing tritium that could then mix with deuterium and lead to high-energy neutron production. The idea is to extract tritium in that layer to reduce the pathway to the most damaging neutron regime.

None of this erases the hard questions—helium-3 availability, plasma conditions, real neutron budgets, materials lifetime—but it explains why D–He³ keeps showing up in the concept’s center of gravity. If the mission is built around short transit and reusability, the reactor has to avoid destroying itself on the way to proving its value.

The 64-Day Mars Architecture: Two Transports, Two Timelines

Mohsen’s Mars concept doesn’t attempt to cram everything into one heroic crew ship. It splits the mission into two transports, because the fastest way to reduce crew transit time is to remove as much load as possible from the crew vehicle. That is exactly how she explains the 64-day number: a design driven by a certain power limit from the reactor, made possible by offloading mass to a separate cargo transport.

“We wanted to design the mission to reach Mars as rapidly as possible because we want to reduce the radiation on the crew. We wanted to take it down to 64 days, which is enough to keep the crew healthy. Any trip that is longer than two months, a lot of damage can occur.” – Layla Mohsen

In the transcript, she states the design logic in plain language: the crew ship is optimized around a health-driven time budget. That quote functions like a mission requirement: shorten the most hazardous part of the journey until it crosses a threshold where health risk is meaningfully reduced.

The cargo transport, in her description, launches around three years before the crew transport. That long lead time isn’t wasted; it’s used to ensure something even more important than speed: that a Mars base is already established before the humans arrive, and that it’s underground to reduce exposure on the Martian surface.

This division of labor stabilizes the entire narrative. The crew ship becomes a sprint vehicle optimized around time, health, and reliability, while the cargo ship becomes an infrastructure vehicle optimized around mass, robotics, and construction. If Starfire is the heart, then “two transports” is the skeleton—the structural decision that makes the rest of the concept hang together.

Mars Before Humans: The Underground Base and the Psychology of a Garden

The cargo ship’s job is not just to deliver gear; it’s to deliver a ready environment. Mohsen describes robotics that build the Martian base underground, and she estimates the construction timeline at roughly six to twelve months. That’s a bold claim—because “robotic underground construction on Mars” is a hard problem—but the mission logic is clear: arrive to shelter, not to exposure.

When asked whether the concept relies on lava tubes or natural cavities, she says the baseline assumption is excavation—digging out structures rather than depending on preexisting caves. The architecture tries to remove “find the perfect cave” as a gating item and replace it with a controlled engineering task, even if that task is extremely challenging.

Then there’s the detail that reveals how the design thinks about humans: the garden. Mohsen doesn’t treat it as a cute add-on; she treats it as mental-health infrastructure, and she frames it as a way to keep long-duration crews functional when the novelty wears off and the habitat becomes “home” in the most literal sense.

This is where the mission quietly becomes more than a transit-time flex. Mohsen describes the goal as building something sustainable that lasts a very long time—more than a temporary habitat away from Earth. In that framing, speed gets the crew there safely, but infrastructure is what makes the presence meaningful.

Landing Like Viking—But With Orbit Capture, Aerobraking, and a Biprop Finish

Fast transit is only half the story; the mission still has to arrive without turning into a crater. In Mohsen’s walkthrough, the landing sequence is described as inspired by Viking, but with a key operational choice: orbit capture first, not direct entry. That suggests an effort to manage risk in stages rather than betting everything on a single atmospheric plunge.

After orbit capture, she describes using aeroshells for aerobraking and then parachutes to further reduce speed. This is classic “use the atmosphere as the brake” logic—because propulsive landing alone scales brutally with mass and propellant. The concept leans on a layered deceleration chain that has decades of Mars landing heritage behind it.

For the final stage, Mohsen says the concept uses an L3Harris Technologies bipropellant engine for navigated landing. The detail matters less as a vendor name and more as a signal: the architecture wants conventional, controllable terminal descent rather than a hand-wavy “fusion lands the ship” shortcut.

She also notes that crew G-limits are not framed as the dominant constraint here the way they can be with short, high-impulse chemical profiles; the implication is a lower, sustained acceleration regime rather than a punishing spike. Whether the eventual profile is continuous or staged, the stated intent is clear: keep the crew sprint fast without turning the vehicle into a ride.

Power as Mission Glue: Electrolysis, RL10-Class Ascent, and the 10-Day Fuel Run

If Starfire were “only” an engine, it would still be transformative—but Mohsen’s mission design leans hard on the power plant role. Once the crew lands, she describes using electrolysis powered by a Starfire reactor delivered by the cargo transport to split Martian water into liquid hydrogen and oxygen.

That LOX/LH2 propellant is intended to fuel an RL10-class ascent approach, with an estimate of about ten days to produce the required fuel. The geographic implication is acknowledged: landing near accessible water becomes strategically important because surface power enables return capability only if the feedstock exists where the base operates.

What’s striking is how candid the concept is about the limits of “make everything on Mars.” When asked about producing enough propellant for the Starfire propulsion system itself, Mohsen notes that while hydrogen can be used in the reactor/propulsion system, producing enough for an ascent engine is one thing—producing enough for the propulsion structure at scale would take much longer and may not be efficient without deeper analysis.

So the near-term picture is a hybrid: the ship carries its reaction mass from Earth for the fast transit and return, while the surface operation uses the cargo-delivered power plant to solve a different problem—getting off Mars without hauling all ascent propellant from Earth. It’s a pragmatic compromise that makes the architecture feel less like fantasy and more like a design that has argued with itself.

The Engineering Bill: Cooling, Cryostats, and What “Early R&D” Really Means

Every fusion-in-space proposal eventually collides with unglamorous realities—especially cooling and thermal management. In the transcript, when cooling comes up, Mohsen points directly to what needs it: superconducting coils and superconducting mirror magnets, plus shielding considerations. Her answer is specific: cooling is “provided in the reactor itself,” with components encased in cryostats that provide the necessary internal cooling.

“Space propulsion is where you can really see its value, because in terms of other propulsion systems, fusion is able to maximize specific power. It reduces the mass specific per unit power by a factor of 10 from solar electric and 50 from fission electric, which enables revolutionary missions like the Mars mission.” – Layla Mohsen

She’s also explicit about maturity. In her framing, the work is very early in R&D, and fusion is still far from being a mainstream terrestrial power solution compared to other options. That statement matters because it puts the Mars vision in the correct category: not “done,” not “next year,” but “this is where the value is if it works.”

In her telling, fusion’s value proposition is strongest where high specific power changes the game: off-grid power, military forward power, and space propulsion—domains where mass per unit power and portability are decisive. That positioning also matches PSS’s broader messaging around Starfire as a compact 1–10 MW system built for use cases where power density is destiny.

This is the bill the concept has to pay to become real: stable plasma performance at relevant parameters, robust superconducting systems, credible heat-rejection strategies, neutron management that doesn’t inflate mass, and a full system that can survive a mission profile measured in months and years. None of that is solved by a great trajectory plot. But without solving it, the 64-day promise never gets a chance to be tested.

If Starfire Works: Mars Stops Being a Stunt and Starts Looking Like Transportation

What Mohsen is really proposing is a different emotional shape for Mars exploration. Instead of sending humans to arrive exhausted and exposed, the architecture aims to have Mars ready—an underground base built by robots, powered by a reactor, with a plan for food production and long-duration habitation. In that framing, the mission isn’t a heroic crash-landing into hardship; it’s a deliberate transfer into infrastructure.

The 64-day crew sprint is the other half of that shift. The mission is framed as engineered to reduce radiation exposure enough to keep the crew healthy, made possible by moving mass to a cargo transport launched years earlier. The mission becomes a choreography of time: slow cargo, fast humans, prepared destination.

The concept also keeps hinting at reusability and tunability—controlling thrust and exhaust velocity to fit mission design—and treats the idea of repeatable interplanetary transport as an engineering trade space rather than a fantasy. In that worldview, the real breakthrough isn’t just arriving faster once; it’s building a system that can do it repeatedly.

That’s the cleanest way to state the bet: if a compact, megawatt-class fusion system can truly function as both engine and power plant, Mars becomes something that can be planned for with more confidence and less bravado. The concept doesn’t eliminate risk; it reallocates it—away from “humans surviving long exposure” and toward “engineering a machine that earns its keep.” That is a hard trade. It’s also the kind of trade that, if won, changes what “going to Mars” even means.

References

Tim Ventura (YouTube) — “Direct Fusion Drive To Mars | Layla Mohsen”

Princeton Satellite Systems (PSS) — “Starfire: Compact Fusion Power and Propulsion”

Princeton Satellite Systems (PSS) — “Fusion Power for a Mission to Mars” (Feb 28, 2025)

NASA — “Risk of Radiation Carcinogenesis” (Sep 12, 2025)