Sandy Kidd’s Gyroscopic Propulsion Device

Some inventions begin as equations. Sandy Kidd’s began as a shove—an aircraft gyroscope pushing back so hard it felt, for an instant, like the machine had a will of its own. The physics is ordinary: angular momentum and precession. The experience is anything but. Out of that mismatch came a stubborn, decades-long dream: to turn a gyroscope’s sideways defiance into lift, thrust, and a new kind of motion—scientific enough to test, strange enough to haunt.

The Legendary Gyro That Started It All

The origin scene is told as a moment of sheer physical surprise. While serving in the Royal Air Force, Sandy Kidd removed a gyroscope from an aircraft and carried it down the steps.

At the bottom he turned, not realizing the unit was still spinning. The gyro reacted with a violent precession torque; in the famous retelling, it nearly threw him across the floor. The story doesn’t need embellishment, because a live rotor can feel less like an object and more like a stubborn thing that refuses to be redirected.

That single bodily jolt is the seed of the mythos. It’s not “a theory that demanded a device.” It’s a device that demanded an explanation—and then demanded, through years of repetition, the chance to become a machine.

Kidd wasn’t a passerby to that world. As an RAF radar technician—trained to trust instruments, procedures, and hard results—he took the shove personally. What might have been filed away as a cautionary tale became, for him, a question worth a lifetime: if precession could hit that hard by accident, what could it do when forced, timed, and engineered on purpose?

The First Dream: Momentum That Could Be “Redirected”

Kidd’s early model was blunt and physical: if rotating masses generate enormous forces, perhaps clever geometry could tip some of that force upward. In his APEC talk, he sketches the intuition with “bricks on strings” reasoning—big centrifugal forces, a tempting angle, and then the realization that reality won’t politely hold the geometry needed to make the trick work.

“My relationship with gyroscopes and inertial drive… was the result of seriously flawed thinking mixed with success born out of sheer good luck.”

— Sandy Kidd (APEC presentation)

Still, the dream had a direction: take the shove of precession—the way a gyro resists being turned—and force it to happen on purpose, again and again, in a controlled cycle. If a single unexpected turn could produce that much reaction in the hands, what might a disciplined machine do?

That dream matured inside a broader cultural atmosphere: the long, noisy history of “inertial drive” claims hovering at the edge of engineering. Kidd explicitly points to the Dean Drive as part of that backdrop—a reminder that internal dynamics can seduce the senses, and that extraordinary claims live or die on measurement.

The Christmas Lectures That Made Gyros Feel Like Magic

In Kidd’s telling, the obsession didn’t grow in isolation. One public moment mattered: Professor Eric Laithwaite’s 1974 Royal Institution Christmas Lectures, a televised celebration of engineering that featured bold demonstrations of gyroscopic behavior.

Laithwaite didn’t merely show gyros behaving strangely; he performed them like characters—heavy spinning wheels that became “easy” to lift in certain motions, and devices that looked as if they were disagreeing with intuition. The lectures became famous partly because they were thrilling and partly because they were controversial: the demonstrations were real, but the interpretations sometimes collided with more rigorous treatments of angular momentum.

The Royal Institution’s archival framing captures the mood: “The Engineer Through the Looking Glass,” a title that practically invites the audience to expect the familiar world to wobble. For an inventor already primed by an unnerving physical encounter with a live rotor, it’s easy to see why this felt like permission to chase the impossible.

Kidd later links that inspiration to commitment. The lectures didn’t “prove” anything about propulsion—but they helped turn a private question into a build-it-and-see obsession, aimed at making precession do more than surprise.

Dundee, a North Sea Oil Job, and the First Vertical Thrust

By the time the legend fully forms, the setting shifts to Dundee, Scotland. Accounts describe Kidd working as a planning engineer for a North Sea oil company, spending nearly every spare minute in a makeshift workshop—essentially a garden-shed lab built for stubborn iteration rather than academic polish.

The dates matter because they anchor the dream in a timeline. Secondary accounts place the start of his anti-gravity/gyro project in 1980, with years of effort before anything that looked like success appeared.

Then comes the milestone that keeps the story alive: at Christmas 1984, Kidd’s machine produced what he described as its first vertical thrust—“not much,” but enough to feel like proof-of-life.

In later recollections, Kidd frames what came next as a scaling problem: once the effect seemed real, the question became whether output could be increased enough to become truly useful rather than merely uncanny.

What the Device Claimed to Be Doing

Kidd’s device is often summarized as “gyroscopic propulsion,” but the mechanism is more specific than the label suggests. The formal version appears in his patent: opposed spinning discs (counter-rotating to manage unwanted torques) arranged in an assembly with geometry that can be forced through a repeatable cycle.

The key idea is time structure. The machine isn’t merely spinning; it’s being driven through a sequence where angular momentum vectors and reaction torques are continually redirected—an attempt to convert “sideways refusal” into an axial bias.

Kidd’s practical descriptions add an unsettling twist: the most effective behavior, in his telling, depended on subtle compliance. In a memorable Q&A recollection, he describes a machine that worked—then he tightened the rivets to tidy the frame and the effect vanished, implying the structure needed to “rock and roll” in just the right way for one gyro to lift the other.

In later framing, he describes the early success less as a single magical trick than as a useful kind of switching: some part of the system effectively turned a force-like quantity “off and on” in a cycle. That idea—switching, timing, and phase—becomes the bridge between legend and engineering, and also the place where false positives love to hide.

The Tests That Built the Legend

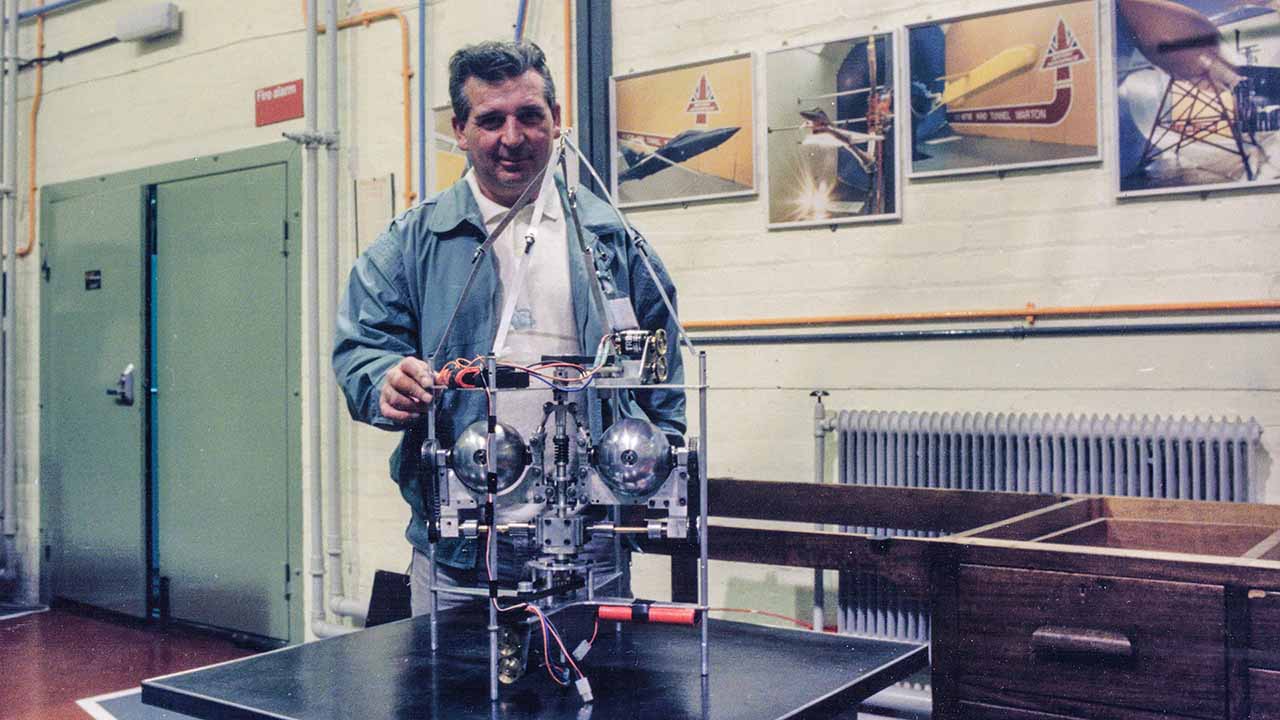

Kidd’s story doesn’t survive on concept alone; it survives on test claims. The centerpiece is the Australian laboratory test device: a compact system built into a closed wooden box, with careful attention to objections—cooling water routed between tanks, exhaust arranged to minimize thrust arguments, and power transmitted by gears and belts.

The measurement centerpiece is suspension and sensing: the enclosed box hung on a cord via strain gauges from an overhead beam. Kidd reports that a series of runs produced consistent “non-zero bias,” small in magnitude but repeatable. He later emphasized that the controversy was rarely about whether the device “did something” during demonstrations—it was about why it could do it, because the mechanism wasn’t visible or obvious.

“There is no doubt that the machine does produce vertical lift.”

— Dr. Bill Ferrier (quoted in secondary accounts)

Skeptical readers see the same setup and immediately list classic failure modes—support-wire dynamics, vibration rectification, resonant coupling, and subtle interactions between a violently spinning machine and whatever holds it. Either way, this is the hinge of the narrative: the point where folklore tries to survive instrumentation.

1987–89: Scaling the Effect — the “Centrifugal Switch” and Split-Sphere Prototypes

After the Australian lab device convinced Kidd the effect was genuine, his focus shifts from proving it exists to making it useful. In his email, he describes the next obstacle as output: whatever the machine was doing, it needed a significant increase in force to become more than an intriguing anomaly. He also distinguishes device generations—his first device and the Australian device had significant operational differences, even if their overall layouts resembled each other.

This reframing also sharpens his view of the early years as an accidental breakthrough. He states that the first machine was demonstrated thousands of times; witnesses didn’t doubt what they were seeing, but they doubted the explanation because no obvious mechanism appeared to account for it. He places a key insight around 1987–88: the thrust, in his view, came from several “non-deliberate factors” that happened to combine.

“With a lot of luck I had accidentally built a working device… In effect, that first machine managed to switch some centrifugal force (or angular momentum if you prefer) off and on in a usable manner.”

— Sandy Kidd (email correspondence)

With that insight, the story takes a distinctly engineering-shaped turn: toward switching and speed. Kidd says that after returning to Scotland he perfected a system first developed in Australia that could turn centrifugal force/angular momentum “off and on” at elevated machine rotation speed—what he calls a “centrifugal switch.” He also points to late-1980s high-speed prototypes: a 1987 “split sphere” unit and a “twin split sphere” unit associated with BAE Wharton circa 1989, noting the design later evolved further.

The Reactionless Drive Lineage: Where Kidd Fits

Sandy Kidd’s name often gets grouped with other “reactionless” or “inertial drive” claims—not because the mechanisms are identical, but because they share the same headline temptation: force without propellant. Kidd himself references the Dean Drive in his APEC remarks as part of the historical backdrop—an earlier controversy that became famous, stayed disputed, and taught the community how easily internal dynamics can masquerade as propulsion if the measurement environment is doing any hidden “work.”

In its patent-era framing, the Dean Drive tradition reads like vibration rectification: oscillation plus timed coupling, a mechanical “diode” that can appear to bias motion in one direction if friction, compliance, and support coupling cooperate. The caution is not that such devices must be fraudulent, but that they can be persuasively misleading—especially when observers rely on feel, sound, or small motions instead of force data under controlled conditions.

Roy Thornson’s inertial propulsion concept sits on another branch: a choreography of eccentric masses whose radius changes under control, producing time-varying internal distributions and impulses. Again, timing is everything—and again, the hard part is showing that any measured bias is not a byproduct of the test stand, the mounting, or the environment responding asymmetrically to vibration.

Kidd’s claim is distinct in mechanical flavor: it is gyro-native. The engine of his idea is forced precession and time-varying angular momentum, not merely unbalanced mass motion. Even where cams, compliance, and cyclic forcing appear, the stated target is the gyroscopic couple—trying to harvest the sideways stubbornness of a spinning system as an axial bias, then pushing toward higher speed and switching architectures to make that bias scalable and testable.

From Legend to Measurement: Proof, Theory, and the Modern Test

Kidd fixed his story in print in Beyond 2001 (published in 1990), presenting it as memoir, argument, and experimental record rather than rumor. In the structure of this narrative, the book matters because it marks an attempt to anchor the claims—especially the Australian lab phase—in a version that can be scrutinized, not merely repeated.

Harold Aspden’s commentary illustrates one sympathetic way the claim has been framed: if anomalous lift exists, conservation laws must still be satisfied, but the “system” might be larger than standard mechanics assumes. In that view, Kidd’s machines are not violations so much as interactions with something unaccounted for—an interpretation that reads as provocative to supporters and premature to skeptics.

Modern science would respond in a more procedural language: the only thing that matters is whether a net force survives ruthless controls. That means vacuum-capable testing (or tightly controlled atmosphere), multi-axis force/torque sensing, vibration spectral mapping, isolation from supports and cables, strict thermal/power accounting, and protocols designed to kill rectification and coupling artifacts—especially for devices that seem to depend on delicate compliance and phase.

Taken together, Kidd’s late-1980s push toward switching and higher-speed architectures reads like an inventor trying to move from dramatic demonstrations toward an engineer’s version of proof: stronger output, clearer timing, and a mechanism he could describe as deliberately “switching” something on and off rather than relying on accidental alignment. The story ends where it began—on a physical jolt that demanded explanation—only now the question is narrower and harder: can the effect be made to stand up in the kinds of tests that decide whether an anomaly becomes a measurement?

References

APEC 7/10, Part #3 — Sandy Kidd Gyroscopic Inertial Propulsion (YouTube)

APEC 7/10, Part #4 — Sandy Kidd Gyroscopic Inertial Propulsion Q&A (YouTube)

Sandy Kidd — “Gyroscopic propulsion” (Rex Research)

Harold Aspden — “Flywheels and Anti-Gravity” (Research Note 12/97)

Sandy Kidd — “Gyroscopic apparatus” (US5024112A, Google Patents)

Roy Thornson — “Apparatus for developing a propulsion force” (US4631971A, Google Patents)

Royal Institution — “The Engineer Through the Looking Glass” (1974 Christmas Lectures)

Imperial College London (Video Archive blog) — “Eric Laithwaite RI Christmas Lectures 1974.”

Sandy Kidd — Beyond 2001: The Laws of Physics Revolutionised (book listing)

The Skeptic (archive) — “The Weight of Evidence: Gyroscopes can’t levitate UFOs.”